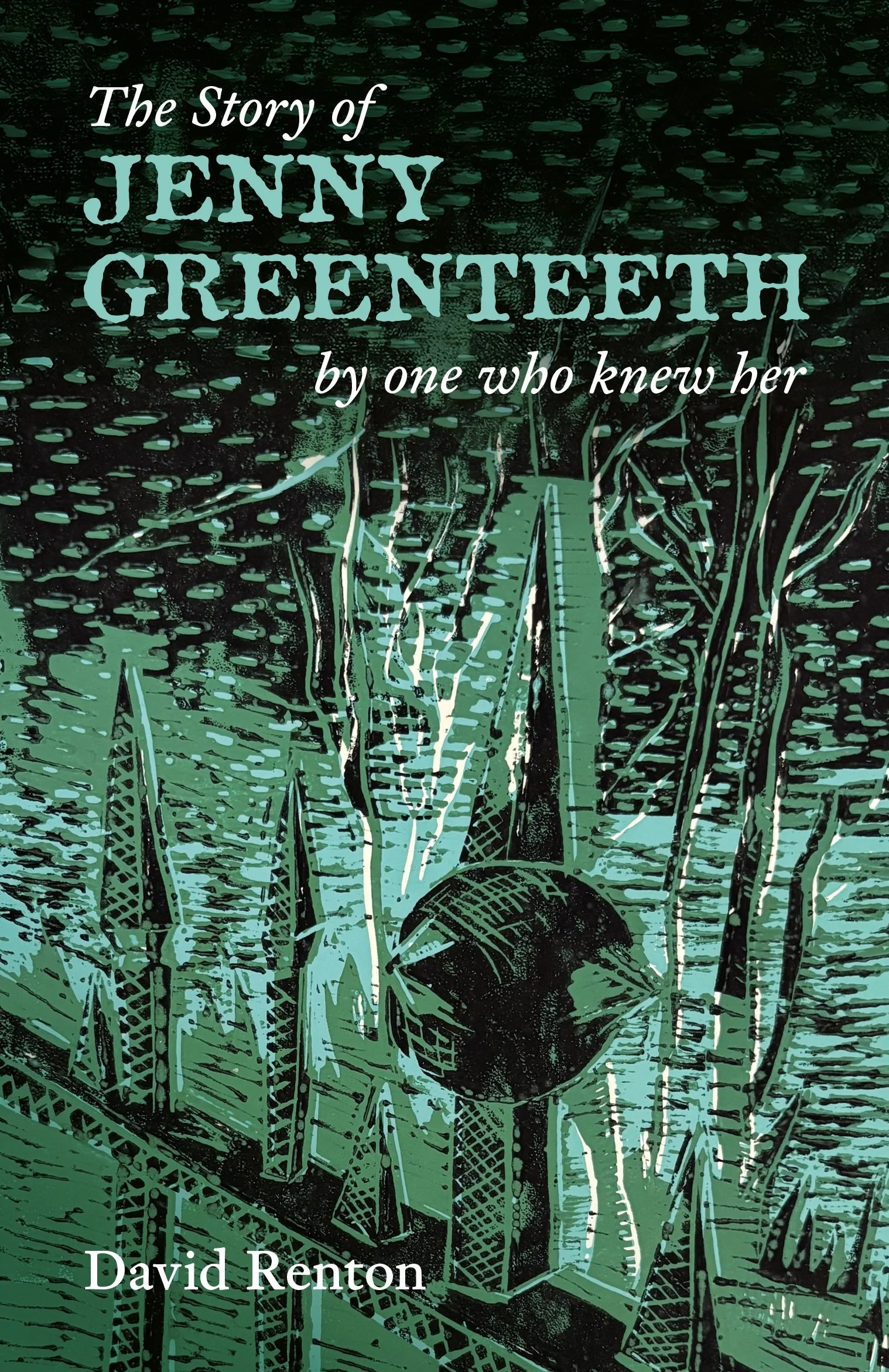

The Story of Jenny Greenteeth

Niamh is studying in London when the boy she loves dies suddenly. She blames herself for his death and can find little relief from guilt, not with her friends, nor in drunken evenings with her landlady Vron. Her life begins to look up when she encounters a woman who lives alone on a north London canal. When her new friend demands that they go to war against all violent men, Niamh must ask herself whether she is ready for that fight.

Vv.m

It is my pleasure to be able to share an extract of the book with you, as part of the blog tour.

This is from the second half of my story. Niamh, my protagonist, has headed north to Chorley, in search of Jenny Greenteeth and the world she lived in.

On the dot of eleven the landlord blew a whistle. Off the doe loped – the people cheering as she did. The road had thick bushes on either side. After fifty metres, the path turned. The woman disappeared round the corner. Boys occupied the line behind which the doe had been crouching. Down they went, like athletes before a relay race. The other children stood back from the finish line, stuck their tongues at the show-offs.

The woman at Niamh’s side was waving her finger and motioning towards one of the boys in the front. “No phones,” she insisted. The boy rushed over, delivered up his device.

The landlord lifted his whistle to his lips, blew.

The boys sprinted at the sound. Within a few metres, they slowed, as if their race had always been to the first corner and no further. Out the sticks came. The rest of the crowd followed. Along the lane they walked, poking with their sticks, bashing wood against branches, hollering, “Come out! Wherever you are.”

Calling this a chase was misleading, Niamh thought, it made you think of races. When the point wasn’t to be fast but thorough. “On!” one of the front-markers shouted, and the crowd quickened. Together, the crowd turned the corner. Onwards the chase went, the children inquiring their sticks into bushes, shouting out as birds fled crying into the sky.

Niamh felt herself entering a dream-state. This was a world of sticks and straw; it was like being inside an antique. She was not in full control of her weight. It seemed to her as if she was no longer in Britain in the new millennium but welcomed back into the past, was living there, was imprisoned there.

The clatter of sticks upon wood. A voice shouting, “Aye, aye, aye.”

Another of the boys cried out, “I’ve seen her! I have! I have!”

“Where?” Faces lifted in excitement.

“An’ you’re sure?”

The boys poked their sticks into the undergrowth.

“No,” they said, their voices desultory.

“You imagined it?”

“I saw her,” the boy said.

“Always one,” his comrade remarked.

One of the younger girls ran for the wildness beyond the hedges. Her mother rushed after her, pointed her back to the procession.

Four times they turned, left, then right; right, then left. The birds cawed above them. On the road led, in a great loop, the sun beating down on them.

“Onwards!” a man cried.

“Keep on,” the landlord echoed, from the back of the crowd. He touched a handkerchief to his sweating face.

Another voice cried, “I see her.”

Then, out of the tall grass where she’d been hiding, the doe strode, deerskin still in place, smoke billowing from her arms. Through the fumes, the children raced. They waved their sticks at the woman, the youngest threw theirs. The teenagers came closer.

The smoke blew away to nothing.

A young woman, tall, slender, was the first to connect. Her bamboo cane swished and hit. Others too. Their attacks broke on the woman’s arms. On her body.

Niamh felt sick. It was the way the woman held herself, still, and uncomplaining, not flinching as the blows landed.

A stick struck her full on the face.

Then for the first time, the woman stirred. “Go!” she cried, another blow snapping on her arm. “By all that’s wild, I command thee–”

Down the blows fell. Clattering like August rain. She whimpered. A nick on her arm blossomed into a red flower.

The woman took half a step forward to right herself. Her gaze went down.

More blows.

The woman flinched for the first time.

In a whisper, the landlord asked. “Who, hag?” He could have been a teacher in the wings of a school play, reminding one of his charges of their forgotten lines.

An older boy came forward. As he did, the others stood, their heads bowed. They knew his part, respected it. Around Niamh, the crowd settled down into silence.

The boy said, “Who, hag? What power do you command?”

“I command no one.”

The boy’s stick struck her cheek. She whimpered. He hit the far side of her face. Blood dribbled down, found the gap in the deerskin, turned her white shirt red.

He struck again. Again. The stick splintered. Its last shards fell to the ground. The woman made a little sob, succeeded in stifling it.